This is the first in a two-part series about U.S. postal history, Tacoma, and Job Carr.

The second post is available here.

In 1845, John L. O’Sullivan wrote, “Our manifest destiny [is] to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions,” (Gambone 2001) and Americans heeded his call. The spillover from burgeoning colonial populations – together with new immigrants – pushed westward by the thousands, seeking fulfillment of their hopes and dreams. These pioneers founded new communities and settled new territories from the mid-west to the Pacific Ocean. As America grew, so too did the communication needs of Americans.

Responding to Changing Times

In 1775, the Second Continental Congress had sufficient foresight to create a precursor of today’s U.S. Postal Service, the “Post Office Department.” This Department linked the various U.S. territorial and colonial populations, large and small, connecting a nation through communication. In its efforts to achieve this end, the Post Office Department proved to be an unstoppable and innovative super force, ensuring that a well-networked nation would stride confidently into the 20th century.

From 1865 until the end of the 19th century, the American population swelled and its cry for mail service did not go unanswered. While the Post Office Department did not maintain records of the number of addresses receiving the mail it delivered, limited records do exist documenting the number of pieces of mail handled, the number of post offices, and its operating revenue and expenses. The following information offers snapshots of the Department’s response to an ever-increasing demand for mail carrier services over those years:

* In 1865, the number of pieces handled by the Department is not available, but we do know there were 28,882 established post offices. The Department’s operating budget showed $14,556,159 in revenue and $13,694,728 in expenses.

* Fifteen years later, (1890) the Department recorded that 4,005,408,000 pieces of mail were handled, and the number of post offices had grown to 62,401. Revenue and expenses for that same year were $60,882,098 and $66,259,548, respectively - a tremendous growth in services in only five years.

* In 1900, as the century drew to its close, the Department handled 7,129,990,000 pieces of mail, and boasted 76,688 post offices across the country. (Service, Statistics: Pieces & Post Offices 2011)

Postage Stamps, ca. 1890 - Job Carr Cabin Museum

Meeting the Needs for a Growing Nation

The increased demand for mail service was created by far more than the increased writing activity in well-established towns and communities. America was experiencing a population explosion. Historians point to high birth rates as the greatest contributor to the population increase, but in the 1840’s, immigration became a significant source. Before 1840, immigrants entered the country at a rate of 60,000 per year, but by 1840 the rate had tripled, and then by 1850, quadrupled. This trend continued into the early 20th century. Many of these people packed their belongings and headed west in search of political and social freedom, wealth, land, or opportunity. (M.Kennedy 1994)

The catalysts for westward movement were varied. The term “Manifest Destiny” was a phrase created in the 1840’s by politicians, political leaders and land speculators as a rallying-cray for the American public. It conjured a mission in the minds of the populace that God had revealed America’s destination to be the far horizon and that they should spread control of the land to the far reaches of the continent. The Louisiana Territory Purchase took place in 1803 (as a result of Spain's ceding of New Orleans to France), adding approximately 1 million square miles to the land holdings of the United States.

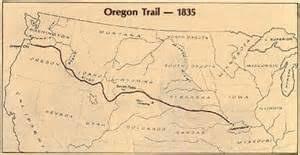

In 1843, the first large wagon-train on the Oregon Trail started what became known as “the great migration,” thus establishing the Oregon Trail as a feasible way to travel over the great mountains. Approximately 5,000 settlers arrived safely in Oregon, having traveled via the Trail. The Homestead Act was signed into law in 1862 – a means of motivating people to move west. The act gave people up to 160 acres of land, and each “homesteader” could claim his land for a nominal fee averaging $30 and the performance of a few simple conditions. Half a million families claimed land and settled the frontier under this act.

Department Design

In order to manage and move the mail effectively, the Post Office Department structured itself on a fairly simple hierarchical design: One Postmaster General oversaw each of the postmasters that were assigned, one per post office. Each of the postmasters managed as many clerks and mail carriers as were needed to meet the demands of their local post office. This framework was established on a national basis, and operated nationally and locally without any interference, guidance, or assistance from territorial or state governments.

The top official of the Post Office Department, the Postmaster General, was appointed by the President of the United States. The local postmaster was subordinate to the Postmaster General. Many postmasters at the largest post offices were appointed by the President (often as a political reward rather than based on any measurable skills or presence of credentials). The positions of postmaster, at smaller post offices or where not appointed by the President, were appointed by the Postmaster General. If a postmaster required replacement, the name of a successor was recommended by the community, a local congressman or by the outgoing postmaster himself. (Service, Postmasters in the Mid-19th Century 2011)

Initially, the Post Office Department oversaw the hiring of one or two clerks for each post office, and was responsible for payment of their wages. All other personnel affiliated with each post office were hired and fired by each individual postmaster, and were paid wages from collected postage fees. Letter carriers received additional monies from charges that they personally collected at the time of letter delivery. By 1865, after free delivery was placed in operation for forty-nine cities, city letter carriers were put on the government payroll and additional clerks were hired to process the increased mail load. (National Association of Letter Carriers 2001)

Job Carr in front of his log cabin, photographed by his son Anthony on 9/3/1866. Note the U.S. flag flying on the front of Job's cabin.

In 1868, residents of Tacoma, Washington were ready for their own post office and petitioned President Ulysses Grant for a postmaster. While stationed in the Washington territory at Fort Vancouver, Grant had seen the need for post offices in the burgeoning West. President Grant appointed Job Carr as postmaster for the frontier town in March of 1869. Job immediately had two decisions to make as the new postmaster: first, determine the site for the new post office; second, appoint a mail carrier. Job’s choices were quickly made; he appointed his son, Anthony Carr, as carrier, and his home as the first post office in Tacoma. By 1888, with the railroad complete, Postmaster Samuel Howse had a staff of thirty-six (clerks and mail carriers). (Tacoma Post Office Began 100 Years Ago In Log Cabin Home Of Job Carr 1969)

Tacoma Post Office Clerks and Carriers, ca. 1885-1890 - Job Carr Cabin Museum

Works Cited

Adminstration, U.S. General Services. Tacoma Union Station, Tacoma. http://www.gsa.gov/portal/ext/html/site/hb/category/25431/actionParameter/exploreByBuilding/buildingId/137 (accessed January 26, 2012).

Armbruster, Kurt E. “Orphan Road: The Railroad Comes to Seattle.” Columbia, Winter 1997: 7-18.

Borneman, Walter R. Rival Rails. New York: Radom House Publishing Group, 2010.

Gambone, Michael D. Documents of American Diplomacy: From the American Revolution to the Present. Westport: Greenwood, 2001.

M.Kennedy, Thomas A. Bailey and David. The American Pageant. Lexington: D.C. Heath and Company, 1994.

Moffat, Riley. Population History of Western U.S. Cities and Towns, 1850-1990. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 1996.

National Association of Letter Carriers. “Postal Record.” nalc.org. February 2001. http://nalc.org/news/precord/0201-mailmillennia2.html (accessed December 8th, 2011).

Ramsey, Guy Reed. “Tacoma.” In Postmarked, Washington: Pierce County, 20-25. Washington State Historical Society, 1981.

Reebel, Patrick A. United States Post Office: Current Issues and Historical Background. Hauppauge: Nova Science Pub Inc., 2002.

United States Postal Service. “Mail by Rail.” usps.com. 2011.

http://about.usps.com/publications/pub100.pdf (accessed January 2, 2012).

—. “Moving the Mail - Steamboats.” usps.com. 2011. http://about.usps.com/publications/pub100.pdf (accessed December 26, 2011).

About the Author: Ms. Pulver graduated from Central Washington University in 2012, majoring in History. Her family lives on Bainbridge Island. While visiting the Cabin on a day-trip to Tacoma, she shared her interest in local history. She was invited to research this topic for a planned exhibit. An abridged version of the resulting document was published in the Museum's newsletter (Eureka Times, Winter 2012 issue.)