This is the third in a multi-part series about the religious affiliations of the Carr family.

The first part about the family Quaker heritage is available at this link.

The second part about the family's Quaker affiliations in the 1800s is available at this link.

The fourth part about Rebecca Carr Staley's Spiritualist journey is available at this link.

An article about Job Carr's association with Spiritualism is available at this link.

Although Job Carr is typically referenced as a Quaker, he and his first wife Rebecca were estranged from the official Quaker church by the 1850s. After this split with the formal church, they each gravitated toward the Spiritualism movement as well as associated progressive social movements for racial and gender equality. The Carrs were among a growing cohort of former Quakers attracted to Spiritualism.

What is the Spiritualism?

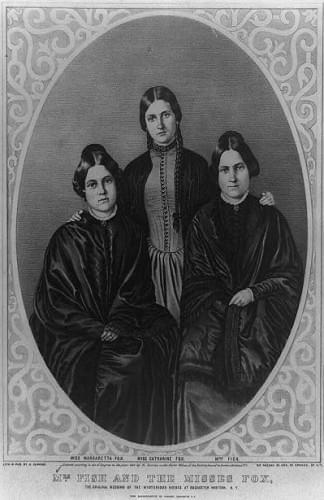

Spiritualism emerged in 1848 spurred by the Kate and Maggie Fox who claimed to have communicated with a dead man’s spirit by knocking and spirit rapping at their home in New York. The Fox family were close friends with Amy and Isaac Post, radical Quakers who were also leaders in the abolition and women's rights movements. The Posts mentored the Fox sisters and became some of the first converts to Spiritualism. After repeatedly demonstrating their alleged ability, the Fox sisters gained notoriety and traveled widely around the United States showcasing their talents. Soon other women began publicizing their own abilities to communicate with the dead via “trance speaking” and started to call themselves “mediums.”

Leah, Kate, and Maggie Fox. Image from "Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women's Rights in Nineteenth Century America" by Ann Braude.

In the 19th century, women in the United States were expected to be modest and pious, giving everything to meet the needs of their family. Social norms dictated that women should keep their opinions to themselves and refrain from speaking out in public. The idealized woman lived by four principles outlined by the Victorian concept of “True Womanhood”: piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity.

The Spiritualism movement, however, offered some women a loophole outside of these social expectations while simultaneously using them to justify the authenticity of their work as spirit mediums. As mediums, women could do things they were not usually allowed to do, incluing speaking publicly to large groups. Women also had the opportunity to attain financial, political, social, and religious freedom. Doing so of course could lead to marital rifts if a husband was against these newfound freedoms. Perhaps not coincidentally, some spirits advised women to divorce their husbands.

Spiritualism attracted women more so than men in part because society generally believed women were biologically suited to mediumship. Women were considered to be naturally weak-willed empty vessels which made them ideal candidates for mediumship as they were to be “controlled” by spirits. Women were not held responsible for their actions while under a trance or channeling spirits through their body. This is one of the many ways mediums used misogynistic stereotypes to their advantage as a way to justify the validity of their work.

Spiritualists had many critics during their time, framing mediums as deceptive “seductresses” whose goal was to manipulate foolish men into giving them money. This criticism led to mediums becoming frequent targets of slander and abuse. The movement also received backlash from the Christian church which labeled Spiritualists as blasphemous. Spiritualism attracted some women, however, because it rejected the Christian doctrine of Original Sin which posits that all people are born sinful. Patriarchal theologians blamed Eve for the creation of Original Sin and as a consequence believed that all women should share her guilt and blame. Many Spiritualists spoke out against Christian theology being used to justify the oppression of women and slavery. This overlap with social justice causes led several southern states to outlaw Spiritualism.

Spiritualism and the Suffrage Movement

The year 1848 was not only the beginning of the widespread Spiritualism movement in New York, it was also the year of the first U.S. women's rights convention in Seneca Falls. Attendees called for the social, civil, and religious rights of women. Several leaders of the women's rights movement overlapped with Quakerism and Spiritualism. As public speakers, Spiritualist mediums also gave speeches about women’s rights, healthcare, gender roles, temperance, and other social issues.

Many prominent public figures became connected to Spiritualism, including Mary Todd Lincoln, the wife of President Lincoln, who regularly held seances in the White House. Also with strong political connections, one of the best known Spiritualists was Victoria Woodhull. Born in 1838, she was raised by her father, also a medium, to delve deeply into the spiritual realm. Taking full advantage of the intersection of women’s rights and being a Spiritualist, Victoria Woodhull became the first woman to open a brokerage firm on Wall Street, to address the U.S. Congress on the issue of women’s rights to vote, and was even the first woman to run for president.

Victoria Woodhull. Image from the National Women's History Museum.

Suffrage and Spiritualism in Washington

Spiritualism quickly spread to the West Coast, where many independent women were defying conventions. In the West, Spiritualism was closely intertwined with the women's suffrage movement. An early proponent of both causes was Abigail Scott Duniway.

Abigail Scott Duniway. Image from the Oregon Historical Society Research Library.

Born in 1834, Abigail Scott came out West to Oregon with her family in 1852 and married Ben Duniway in 1853. Scott Duniway became a teacher, a milliner, and a mother to six children before answering the call of women’s rights. She campaigned throughout Washington and Oregon and became known as Oregon's Mother of Equal Suffrage. Her efforts bore fruit in 1883, when Washington state became one of the first places in the world to grant women the right to vote. In December of that year, 191 Tacoma women cast their ballots electing the new mayor and city council. Although women's suffrage was reversed by the Washington Supreme Court just four years later, the movement continued to gain traction

Less talked about is Abigail Scott Duniway's support of Spiritualism. The close connection between Spiritualism and feminism angered her critics, but she staunchly defended it as a valid religious experience. Scott Duniway lived out the rest of her life fighting for equal rights but died before the 19th Amendment gave women across the country the right to vote. She reflects the typical demographic of a Spiritualist woman, as well as those in support of women’s suffrage and the abolition movement. Usually, women in the Spiritualist movement were young, white, Protestant, and unmarried. With progressive views on civil rights issues, however, the Spiritualist movement also found proponents in the black community, including Sojourner Truth.

Working alongside Scott Duniway as an advocate for women's rights was Lucy Childs Bradish, who moved with her family from Oregon to Tacoma in 1873. As part of the next generation, Lucy's daughter Estelle Bradish was one of many beneficiaries of the ongoing fight for equal rights. Estelle worked as a newspaper journalist, became the first woman in Pierce County to serve on a jury, operated her own business as Tacoma's first florist, and served as Tacoma's first female public official.

"I had always, since I was a girl, rather talk of the things men talk of than of those which women are supposed to monopolize."

-Estelle Bradish Mann, 1899 interview

Find out more about Rebecca Carr Staley's involvement with the Spiritualism movement in the next article in this series.

About the Author

Kristin Luippold began working as the Volunteer & Visitors Coordinator at the Job Carr Cabin Museum in 2021. She has lived in Tacoma for most of her life and graduated from UWT with a focus on International Studies and Art History. After spending most of her career in the nonprofit sector and performing arts sectors, she is thrilled to combine her love of history and the volunteer community by working at the Job Carr Cabin Museum.

About the Research Contributor

Gabi Sutton is a student at Pacific Lutheran University, majoring in history and minoring in psychology and religion. She completed an internship with Job Carr Cabin in Summer 2023. After graduation, she wants to pursue a career in the museum industry.