This multi-part blog series discusses important Black figures in early Tacoma history. It underscores their

contributions to the city’s history. These men and women helped shape and develop Tacoma, providing lasting impacts that can still be seen today.

This first article is about the Conna family who were the first Black family to live in Tacoma.

The second article is about George Putnam Riley who was the first Black investor in Tacoma and will be available soon.

The third article is about Nettie Asberry, a leading Black voice in Tacoma history and will be available soon.

The First African American Family in Tacoma

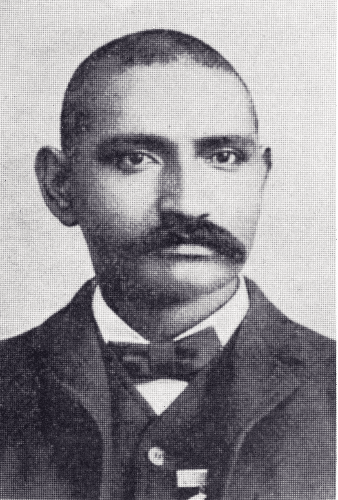

Photo of John Conna, ca 1890. From the Northwest Room at the Tacoma Public Library, General Photograph Collection CONNA-001.

The Conna family was the first Black family to establish residence in the Tacoma region. John Newington Conna was born into enslavement in Eastern Texas in 1836. He escaped to New Orleans about

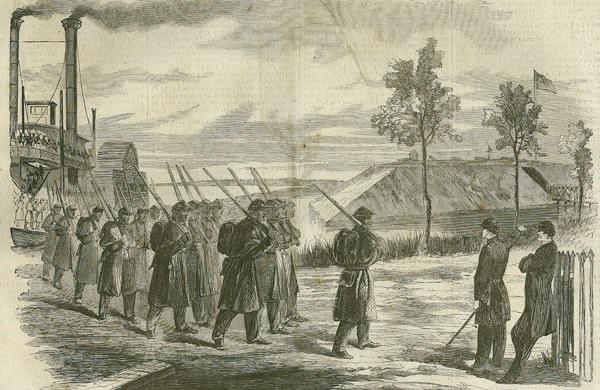

1860. After the capture of New Orleans by the Union Army in 1862, John decided to enlist in an all-Black Civil War regiment as a private. He fought in battles both in Louisiana and Mississippi.

The First Regiment of the Louisiana Native Guards disembarking at Fort Macomb, Louisiana. Published in Harper’s Weekly.

After the Civil War ended, John moved north. In 1869, he met Mary Louise Davis who had been born and raised in Connecticut. She had black and Indigenous heritage. They soon married and started a family. John began attending night school and found work as a porter and in the insurance industry. About 1877, John, Mary, and their seven children headed west to Kansas City, Missouri.

Photo of Mary Davis Conna, Published by HistoryLink.org courtesy of Douglas Q Barnett.

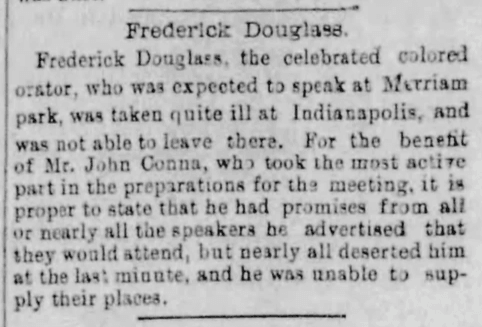

The population of Kansas City boomed after the Civil War including an influx of freed Black people migrating from Southern states. The Connas added two more children to their family and were involved in several community organizations, including as founding members of the St Augustine Episcopal Church. John served as a Grand Master with the colored Masons, conducting Masonic rites when the cornerstone of the church was placed in 1882. John became active in real estate transactions in the city, as well as local politics. In 1880, John coordinated a public event where Frederick Douglass was expected to take the stage. Unfortunately, Douglass fell ill en route and was forced to cancel his appearance.

Frederick Douglass is unable to appear at an event coordinated by John Conna, Published in the Kansas City Journal on September 11, 1880.

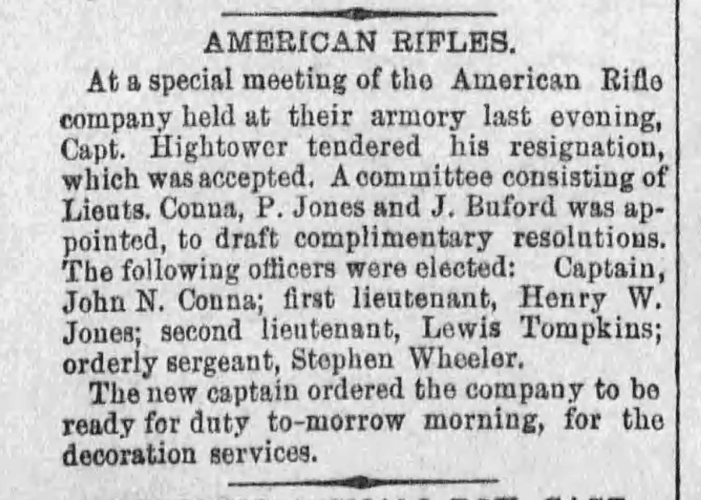

Although, Missouri did not secede during the Civil War, slavery was legal in the state until 1865. After the war, backlash against reconstruction surged. By 1880, former secessionists led Missouri’s congressional delegation and state legislature. The Connas and other Black residents faced discrimination and segregation. In 1882, John joined a committee to investigate abuses at the colored school but wrote a letter to the Editor of the Kansas City Journal that their efforts faced “almost insuperable obstacles thrown in its way by parties interested in suppressing the investigation.” The Black community also dealt with the threat of mob violence and lynching. John joined a unit of the Missouri National Guard and served as Captain for just over a year, providing security in this volatile environment.

American Rifles announcing the election of John Conna as Captain, Published in the Kansas City Journal on May 30, 1882.

In 1883, the Connas decided it was time to move further west. John and Mary and their children were the first African Americans to travel by train to Tacoma on the newly constructed railroad line. John purchased a 157-acre plot in Federal Way as part of the government’s land grant program for Civil War veterans. The family lived on this land seasonally from 1885 to 1891. The property had a log cabin home, two wells, chickens, horses, fruit trees, and vegetables. Mary often managed the farm and homeschooled the children while John was traveling.

John soon got a job in Tacoma working as a real estate agent with Allen C. Mason, and became the leading broker. He worked in Mason’s office in Old Town Tacoma, located on N 30th and Carr Street. By 1890, he opened his own real estate office in downtown Tacoma on A Street, also known as the Mason Block, and may have had a second office in Old Town. Throughout his real estate career, he bought and sold many properties across the city. He also served as lessee and manager of the National Guard facility (later the Tacoma Armory), and added two additions to the city, the first near the current location of Sherman Elementary and the second by Fort Lewis. He actively recruited African Americans from other parts of the country to migrate to the Pacific Northwest, placing ads in East Coast newspapers that encouraged Black workers to move here.

Tacoma Power Old Town Substation on N 30th St was formerly the location of Allen C. Mason's real estate offices where John Conna became the leading broker.

The Connas were also the first Black family to live in the growing city of Tacoma. They purchased a home just uphill from Old Town at 1109 North I St, where Lowell Elementary is now located. The family continued to grow; Mary gave birth to 4 more children in Tacoma. The Conna children could attend the same schools as their white neighbors. John continued to attend night school and gained the knowledge to practice as an attorney. Their home was the site of family celebrations and tragedies. In 1895, the family hosted the wedding reception for their daughter Mamie at their North Slope home. She was married at St Luke’s Episcopal Church and nearly 200 invitations were sent out for the event. Just a few years later their 16-year-old daughter Bessie died at home from spinal meningitis. By the time of Mary’s death in 1907, only six of the 14 Conna children were still living.

Obituary of Mrs. John Conna, Published in the Seattle Republican on July 26, 1907.

John was a leading voice for the Black community in Tacoma. He took a dynamic role in local community

organizations, including leadership roles in the John Brown Republican Club, the United Order of Odd Fellows, and the Washington State Protective League. He joined the local Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Chapter for Union veterans. The GAR was one of the few integrated organizations in the country, providing veteran support after the Civil War. He was also a member of the Afro-American League, the precursor to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Brief Tacoma News announcing the re-election of John Conna as president of the John Brown Republican Club. Published in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on September 11, 1892.

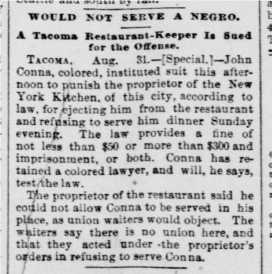

John was active in Washington politics. When Washington became a state in 1889, he was the first Black person appointed to public service, filling the role of Sergeant At Arms for two years. Like Job Carr, he spoke publicly in favor of women’s suffrage. He also used his legal knowledge to advocate for others, including writing and lobbying for a Public Accommodations Act in 1890, which made it illegal to discriminate in public places in Washington state such as restaurants and hotels. To test the law, he successfully sued a Tacoma restaurant for refusing to serve him.

Would Not Serve a Negro: A Tacoma Restaurant-Keeper Is Sued for the Offense. Published in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on September 1, 1891.

In 1896, gold was discovered in Alaska. John was caught up in the frenzy. He pooled his money with three other leading Black businessmen to establish the Seattle Klondike Grubstake and Trading Company. He tried to convince his family to move north but they declined. In July 1900, 64-year John boarded the SS Seattle for Alaska. He settled in Fairbanks where he continued to pursue interests in real estate, mining, and politics until his death in 1921.

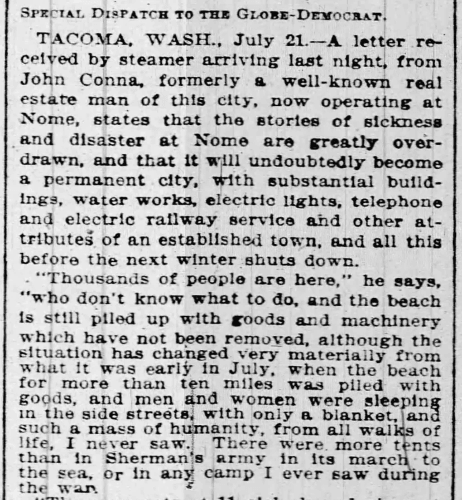

Letter from John Conna soon after his arrival in Nome, Alaska. Published in the St Louis Globe-Democrat on July 22, 1900.

The story of the Conna family faded in the following century. While several members of the family, including Mary, are buried in Tacoma, their descendants slowly dispersed across the globe. In the past 10 years, the family’s efforts and local historical researchers have unveiled the crucial role that the Conna family play in Tacoma and the region’s history.

About the Author

Charlee Dobson Cohen completed an internship with Job Carr Cabin Museum in summer 2025 as a junior at University of Puget Sound majoring in History and Art History and minoring in African American Studies and Study of Consciousness. With this, she hopes to go into curatorial work in museums.